In January, my brother and I are going to see Kool Keith at a storied Toronto venue for twenty five dollars (plus fees). I’ve been a Kool Keith fan for something like 28 years, when he was giving producer Dan the Automator his start with his persona Dr. Octagon (to whom I will be returning), then, either as himself or more personae than even Will Oldham could possibly imagine, he has put out at least 20 albums on his own. This in addition to manifold singles and EPs and dozens more album length collaborations with Ultramagnetic MCs, Cenobites, and my favorite, his dynamite collaboration with Ice T, Analogue Brothers. I will also be engaging Ice T's work in these pages. I’ve got to say I’m pretty excited. The last time I saw Kool Keith live was in a performance space, Higher Ground, outside Burlington, Vermont about 25 years ago, give or take. He wore his Black Elvis pompadour and threw fried chicken at the audience.

Yet in 1996, with his Dr. Octagon LP on the storied Fat Beats records suddenly picked up by Dreamworks, Kool Keith was in the vanguard of a burgeoning movement in hip-hop. This was what was later both self deprecatingly and pejoratively referred to as “backpacker” hip-hop, and indeed had a lot of middle class white fans (looking at myself again here) but even moreso, was the hip-hop equivalent to what used to get called “college rock”. It was nerd-boy music, albeit with radical left and anti-imperialist politics. A contradictory form, the “backpacker” label does not do justice to the plethora of styles and traditions that were captured under that label, like “alternative”, “jam band”, “electronic dance music” and so on, captures the limit of the concept of genre. Indeed, the constellation of disparate artists who came to constitute the architectonic of “backpacker” hip-hop” was curated by a label, Rawkus Records, bankrolled by the son of Rupert Murdoch, one James Murdoch and two of his high school buddies. Rich kids. And when the money stopped trickling in, Murdoch cut the chord.

“Backpacker” hip-hop’s social base and fandom, however, was largely grassroots, not even mainstream in hip-hop’s own capitals like New York or Los Angeles. You needed to go to stores like Play De Record in Toronto or other spots, get mixtapes from behind the counter - Tony Touch was an all timer in my books. You had to read Alt.Music.Hip-Hop (or was it hiphop?) on Usenet - if you know, you know. It was an alternative even to the alternative, as it wasn’t simply “conscious” rap. A lot of it was grimy party music or only a few steps away from some of the more aesthetically adventurous “mainstream” hip-hop artists of the period like the vast Wu Tang International, Mobb Deep or the Native Tongues collective (Tribe Called Quest, De La Soul, Jungle Brothers and so on). Indeed it can likely be aesthetically situated somewhere between the two. pushed itself, via canny marketing and charismatic proto-stars like Mos Def (now Yasin Bey). Like everyone else, I first heard him stealing the show on De La Soul’s Stakes is High.

Then there was the single, “Universal Magnetic”, which standing on its own two feet is an all time banger. It slaps, a song of the summer for ‘97. After introducing himself, we move into ingenious and playful wordplay, in an unironically nor ostentatiously old school style, with 80s single tone inflections and an 808 drum machine. After this old school overture, a soulful beat comes in, while Yasin Bey starts by paraphrasing Afrika Bambaata’s “Planet Rock”. A song that venerates its predecessors while veritably inventing a new sound while reinforcing the tradition of the 'b-boy’, the breakdancing element among the four elements of hip-hop culture, along with rapping, DJing, and graffiti. "“Universal Magnetic” and its classic b-side “If you can huh you can hear” both appear on Soundbombing, and are to a large extent a centrepiece to this new kind of album.

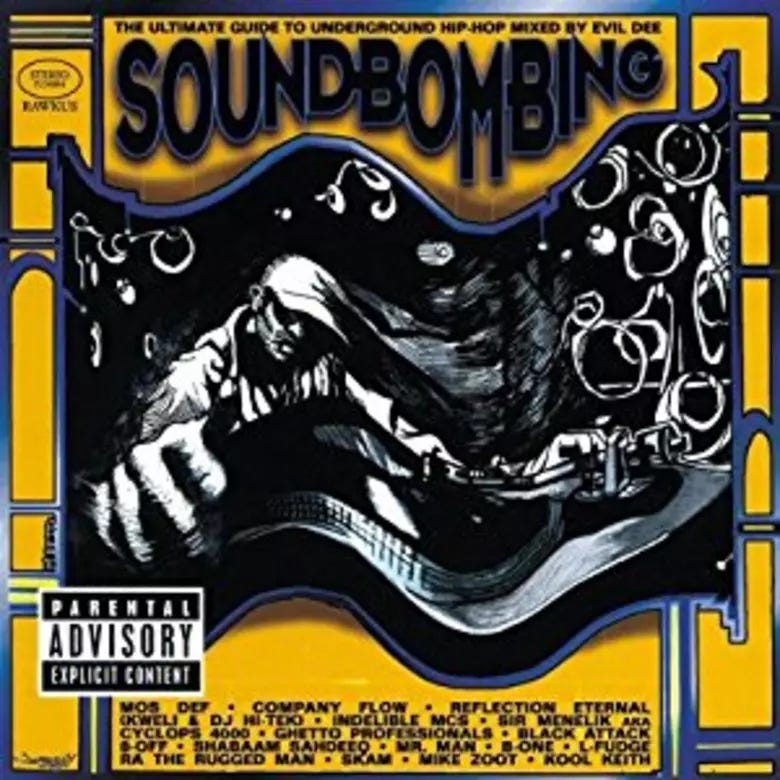

Following the success of the mixtape form, much of which, back in the day, was literally recorded on the spot, with the MCs performing live in a studio, or for a small group of friends, the mixtape-as-album started to be a thing. In mainstream hip-hop, you’d have FunkMasterFlex, among others. None were as legitimate to the culture as were those that were put out by labels like Fat Beats, Stones Throw, and Rawkus. This itself promoted a miniature renaissance of Canadian hip hop - notably from the Raskalz, Saukrates, and Choclair, the latter of whom was sampled by DJ Premier of Gang Starr on the iconic “You Know My Steez”. Rawkus in particular had a dynamite run of mixtape-albums, with the Soundbombing and Lyricist Lounge series, all of which are at the very least solid, and in this case a masterpiece. They also put out singularly brilliant records by Black Star, Mos Def, and Company Flow.

This volume of Soundbombing is probably the best, even if the Lyricist Lounge volume is a bit more of a fun listen. Even Robert Christgau gave it an A minus! It is also the one that set the template for mixtape concept albums to this day, and the one that made me take interest, hence its inclusion here. I think I heard about it on Alt.Music.Hip-Hop. I remember picking it up at HMV, of all stores, in downtown Montreal, where I was doing my undergrad at the time. They got in all the “imports” and there was no equivalent to Play De Record that I knew about. Of course it wasn’t a real mix tape. It was (and is) a CD, and most of the songs were written for it or were recent Rawkus singles. In that sense it was a compilation using the mixtape form. As of now it is not in print, nor is it even on Spotify or other streaming services. One can approximate a playlist with most of the tracks, albeit not the same versions, and more specifically, not with DJ Evil Dee mixing the tracks.

Soundbombing kicks off brashly with a sort of theme song from “The Brick City Kids”, an alter ego for one of the great underground hip-hop groups at the time, the Artifacts. This leads right into a short impressionistic performance, the first of two, from the inimitable R.A. the Rugged Man. With the grimy tone, as much Wu Tang and Primo as Tribe and De La, and with its braggadocio, this was immediately situating Rawkus, as Allmusic’s Nathan Raban puts it, as the “Anti-Bad Boy”, a reference to Sean Combs’ label, featuring the late Notorious B.I.G., himself, and the very oddly named “The Lox”, among others. Of course, good underground MCs freestyled over The Lox’s “All About the Benjamins” instrumental, as that’s a dope fucking beat. It can be said, with quite a bit of certainty that the Rawkus crowd was not at Puff Daddy’s white parties. They were more likely to be hanging out in ‘cyphers’ with cultural icons like Saul Williams, who appears on Rawkus Lyricist Lounge LP.

We soon move into a series of tracks from the artists who alongside Yasin Bey and his crew, were the prime movers for Rawkus in the early days. This was Company Flow, and in particular, one of its MCs and its producer beat-maker, El P, now one half of Run the Jewelz. These tracks, first from Indelible MCs, a supergroup comprising Co-Flow and associates, followed by the utterly exceptional Co-Flow track, “Lune TNS”. The kind of vocal gymnastics exercised on both these tracks, and the following one from Kool Keith associate Sir Menelik (and produced by LP), are all directly informed by Kool Keith in terms of lyrical complexity. Along with artist later known as MF Doom, Zev Love X from KMD, Kool Keith was the elder of this kind of hip-hop, as well as an enthusiastic participant, picking up a whole new audience.

Unlike traditional hip hop, Kool Keith and others that followed didn’t and don’t rhyme either on the beat or against the beat. Indeed, aside from having a similar tempo, rhyming here is only tangentially related to the beat, hence the tonal minimalism of the production work of the likes of El P, Dan the Automator or Kutmasta Kurt. There may be times in which the beat seems to match the vocal delivery, as on what ends up amounting to a chorus - often a chant-like repetition or a sample. This particular kind of vocal performance is now somewhat common, but performed in an entirely different context. Wordplay reminiscent of early George Clinton, prog-rock, the Beatles and sometimes the cutup style of William S. Burroughs is almost the norm in more aesthetically adventurous hip hop spaces, as are breaking sonic rules. Take the recent work of Lil’ Yachty, for example.

Kool Keith’s only contribution to this album is alongside Sir Menelik on “So Intelligent”, a sterling example of this type of wordplay, from Baboon flatulence to obscure Tom Cruise references. The two later worked together extensively, in particular when Menelik unexpectedly changed his moniker and persona to Scaramanga, after an obscure, three-nippled Bond villain. It’s trolling on vinyl before the term was properly known - lyrical delivery at best approximating a sort of abstract expressionism, quite literally, but with plenty of thought, for example, towards as many multi-syllabic words as possible. Then the chorus, back and forth from Kool Keith and Sir Menelik: “You think you’re smart?” “So Intelligent!” Postmodern signifiers neither floated nor were fixed, yet seemed to be a mix of both.

This - the broader participation in the 90s trend of pastiche, in the main, is the primary charm of 90s underground hip-hop, and why it can never be truly replicated. There are plenty of innovative hip hop artists right now. But it is responding to something different, and the age of spotification no longer allows for the same kind of cult-to-mass sensation. The legacy, however, of, for example, Kool Keith, with his personae and perhaps ambiguous sexuality is instantiated with the work of Tyler, the Creator at least stylistically. Tyler does not have the frame of reference, nor the raw working class skills though. Now based in Germany, R. A. the Rugged Man is still putting in work, branching out to make horror films and be an all around hip hop mensch. Talib Kweli and Yasin Bey are somewhat past their prime, having recorded another Black Star album without DJ Hi-Tek. Ironically Talib Kweli did a very good record with Styles P of former Bad Boy associates, The Lox.

This year, one of the most aesthetically one-sided yet clarifying instances in hip hop history occurred. The 'battle’ - which I put in quotes as Drake cannot even hold a lighter, let alone a candle, to Kendrick Lamar. Though firmly a west coast artist, Lamar’s mellifluous rap skills transcend coastal or regional styles, while Drake is ersatz Toronto. This set off, however, a sort of practical debate within the culture - and there’s no doubt some talented artists who originated well outside the New York/LA/Atlanta triad of the 90s- Lil’ Wayne, for one. That being said, Lamar asserted Drake was “not like us”, and to wit, a “colonizer”. The YouTube video essayist FD Signifier has a brilliant (and long) video essay giving broader context than I could ever give here, but what is notable is that, after Soundbombing, a certain Kanye West started to make himself known in and around the “backpacker” milieu, before some significant social climbing. And now Jay Z tries to look like Basquiat while saying “capitalist” is a slur.

Looking back to the challenge that not just Rawkus and company, but also Wu Tang Clan, Native Tongues, Mobb Deep and so on, presented to the “Rap and Bullshit” of Diddy et al, one wonders if it was kayfabe. Kayfabe, for those unaware, is a term from professional wrestling that basically amounts to the maintenance of the illusion and the suspension of disbelief. This allowed fans to route for the “face” and boo the “heel”. There were aesthetic differences of course, but I was not alone among hip-hop heads in being on the road that summer with Wu Tang Clan’s new one, Tony Touch mixtapes with Rawkus singles -and Puff Daddy and The Family’s classic debut. They were characters, of course. Note - this is not to speak of the Death Row/Bad Boy rivalry, which I may revisit in an entry on Dr. Dre and Death Row. That was - not - Kayfabe. And ironically, Suge Knight was an absolute piker, it seems, compared to the (not the good kind of) gangster, Sean Combs.

With the Drake/Kendrick Beef, it was purely about the art and “the culture”, as it were. To a large extent, it was about class even more than race. Lamar was proletarian, with a reputation of being the troubadour of Black Lives Matter. Drake is Will Smith with even less talent, but, if I’m being honest, can write good hooks. I often wonder how a Drake song would sound in the midst of Soundbombing. Would sing-songy vocals and inane lyrics be any different from, say, Mos Def and Nate Dogg’s “Oh No?” on a later volume. Perhaps not. The sound, after all, of authenticity or inauthenticity is entirely context-dependent. And when we move past the specific context in which there are black hats and white hats, heels and faces, we can assess, according to a standard criterion what constitutes genuinely good art. This is what allows for a revisiting of seemingly stayed and mainstream artists of the sixties, from The Fifth Dimension to the Monkees. This, in turn, is indicative of my prediction that Drake would always sound out of place alongside Sir Menelik and R.A. the Rugged Man. As the latter says, “We not like you other MC's riding fake props. I'll be in this rap shit till my fucking heart stops.” To paraphrase Huey Lewis and the News, the underrated 80s pub rock band somewhat discredited by Brett Easton Ellis, if perhaps the heart of rock and roll is no longer beating, certainly the heart of hip-hop is alive and well.