"I think it's limiting. I'd rather just be known as a progressive rock band from the South. I'm damned proud of who I am and where I'm from, but I hate the term 'Southern rock.' I think calling us that pigeonholed us and forced people to expect certain types of music from us that I don't think are fair." Dickey Betts, Allman Brothers guitarist on the concept of ‘southern rock’

When one hears the term “prog-rock”, one usually thinks of odd time signatures, subtly non-traditional instrumentation, virtuosity, but also, the music of those with a “progressive” mindset. That is to say, “progressive” could connote politics, among other things. With perhaps the only exception being the ignorable Randroid libertarianism of Rush, musicians of the first generation of prog-rock had progressive politics, and this imbued their music. Think of Genesis’s anti-landlord “Get ‘em out by Friday”, in particular. Others may have been psychoanalytic or ethereal, but having progressive politics was as co-constitutive with what was being labelled by DJs, A&R men and promoters as “progressive rock” as were the time signatures and so forth.

And it was for this reason, it seems quite clear, that the Allman Brothers saw themselves as progressive rock. Indeed, this is implicit to the case I am making here, to posit the link between the Allman Brothers and, Genesis or King Crimson. Indeed whatever are the manifold flaws with regards to the concept of “jam band” - it was a far better descriptor for the late period Allman Brothers than the insipid “Southern Rock”. But “jam band” itself is an imprecise category, connoting specifically the US northeast market and other “hippy” milieux, including bands that didn’t do much improvising, but ostentatiously excluded Sonic Youth, Godspeed, You Black Emperor!, shoegaze music in general and others who used improvisation in a far more adventurous way than the likes of String Cheese Incident. On the other hand, as I will argue here and elsewhere, not only the Allman Brothers Band, but the Grateful Dead and - perhaps more clearly - Phish, were or are bands that can be concretely situated in the progressive rock tradition.

No better example of the Allman Brothers being a prog band can be found than on what is probably their masterpiece, and certainly the album that sent me down the Allman Brothers rabbit hole, Eat a Peach which was issued and partially recorded right in the wake of the death of guitarist Duane Allman in a motorcycle crash on October 29 1971. The narrative of the album (which is alas, altered by its CD and digital reissue, or perhaps recast), allows us to see the circumstances of the surviving Allman Brothers Band, with only one remaining brother. The first three songs, recorded in the studio are without Duane Allman, they reveal a different sounding band, albeit one that could play to its strengths. They were more keyboard prominent in the passionately performed “Ain’t Wasting Time No More”. “Melissa” in particular is an iconic Greg Allman ballad, while “Les Brers in A minor”, a Betts instrumental is a great improvisational template. The sort of ambient, even Eno-esque section at the beginning of the track is a hidden prog connection without a doubt. The playing is pure psychedelic mourning and it is where we first are clued into the prog quality of the music.

In the Allman Bros’ instrumental palate, sophisticated composition is not based, like a lot of first generation British prog rock on exogenous development, after a fashion, initially of Pete Townsend with the Who, and later the work of Genesis and so on. It was more like another band that is historically seen as having transcended the “prog” label, Pink Floyd. Both were consciously blues based, though this is where they parted ways. What was key is that improvisation and complex composition were inextricably intertwined in Pink Floyd’s early work, as they were with the Allman Brothers, right from their debut. And of course, there were time signature shifts (“Dreams”), poppy acoustic songs (“Midnight Rider”) and mournful sounding and morbidly named instrumentals (“In Memory of Elizabeth Reed”).

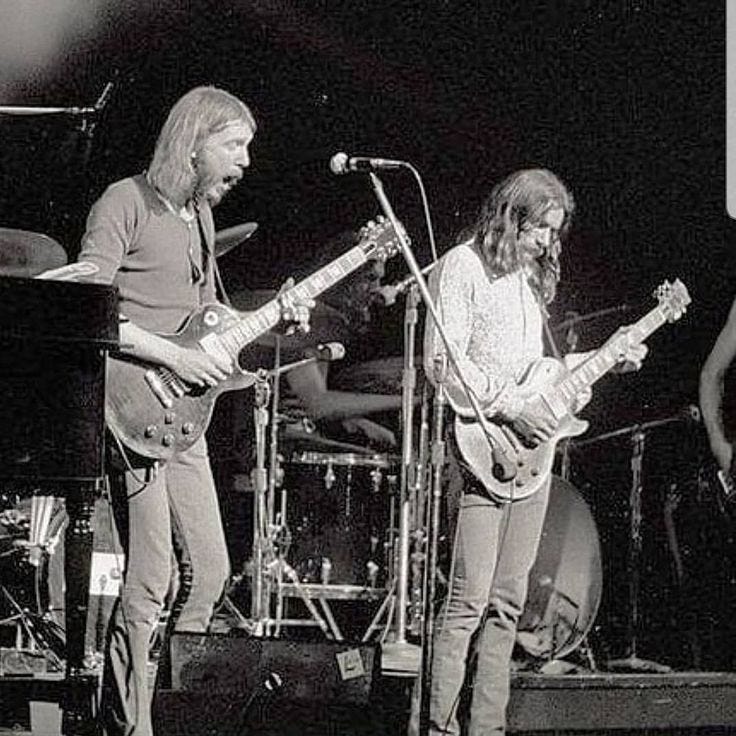

What was ‘progressive’ here comes primarily from the latter. “Elizabeth Reed” is notable for providing a template, not just for the Allman Brothers but in general to the art of dual lead guitars. Not just having guitarists switching between lead and rhythm but dual leads. Duane Allman and Dickey Betts consciously saw themselves as taking on, respectively, the John Coltrane and Miles Davis roles. Yet their own routine was sui generis. One of them, usually Betts would play a lick - either a composed part or, as was often the case, a piece of improvisation, or a piece of improvisation that became a composed part. Then the other, usually Allman, and sometimes with a bottleneck slide, would double Betts with a few second of delay and subtle harmonics. But they were not playing counterpoints, they were playing together. Notably the Allman Brothers’ drummers, Jai Johanny (Jaime) Johnson and Butch Trucks also played in unison, a big four armed drum squadron, as opposed to, for example, the Grateful Dead’s “rhythm devils”, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzman.

After the story begins, as mentioned with the three posthumous studio tracks, we enter the first half of what is called, on record, “Mountain Jam”. This was a long piece of improvisation based around the Donovan’s Brit-folk “There is a Mountain”. The Grateful Dead (on the album version of “Alligator” among other places), and others had jammed on this irresistible theme for years, as had the Allmans. Donovan’s vocal melody, from high to low to high is a perfect match for Allman and Betts’ guitar style and the texture is perfect for Gregg Allman’s Hammond B3. The version on Eat a Peach is a sort of invitation, to quote a later Allman Brothers song from their 90s iteration, “back where it all began”.

We start with a sort of ethereal or ‘space’ like introduction to the main mellifluent theme of “There is a Mountain”, with Duane Allman and Betts, along with bass player Berry Oakley playing circles around each other. Getting into hard bop/prog mode, Duane Allman’s confident swaggering solo is hot out of the gate and, in lieu of going to hyperspace, faithfully riffs on Donovan’s vocal melody, with Betts swirling around him, alternately mimicking/echoing or adding dissonance and power chords. Gregg Allman’s long organ solo follows, with similar interplay from the guitarists, followed by Betts’ own solo, in which the song starts going into what Phish fans later labelled “type II” improvisation. This is improvisation that is not only vamping within a given structure, but in doing so, changing that structure. While not as viscerally mind-blowing a player as the late Duane, Betts as much as anyone had the ability to use unorthodox improvisation to proverbially conduct the band. The once the new structure is in place, the “mountain theme” returns, in a form of dialectical musicianship, in other words, before we slip into a drum solo.

And so ends the first visit to the mountain. It is notable that this is where the LP version is canon, and the compact disc/digital version is a shanda, something that completely alters the narrative. As opposed to the narrative being situated around coming into and out of “Mountain Jam”, on the CD, the entire Mountain Jam is there at once. This has the effect of perhaps exhausting the listener before they get to more live material and Duane Allman’s final studio tracks - side 3. It also takes these final studio tracks out of their proper context. The listener has been taken from the Allman Brothers’ new sound with only one guitarist, through to the first half of their cornerstone improv piece (from the same set of shows that produced their previous, masterful Live at Fillmore East). Then, part of the way through that, we hear the old band back in the studio.

Two more live tracks appear here, notably traditional electric blues, Sonny Boy Williamson and Muddy Waters covers respectively. We have a rave-up (“One Way Out”) and a very Allman-Prog arrangement of “Trouble No More”. The latter had its own riff, as much redolent of the Allmans riffing on British hippies playing flute as anything else. And here we arrive at more studio tracks. “Stand Back” is apparently Duane Allman’s final recording and his playing, on a funk organ driven track by his brother is an apt swan song, going out swinging. What follows is more famous, and perhaps Dickey Betts’ greatest vocal-driven song, “Blue Sky”, played often recently due to his own departure. “Blue Sky” is a near perfect country rock song, the template for what Betts tried to imitate from himself on the later, somewhat inferior but fun “Rambling Man”. It is also a final example of the classic double lead battles between Allman and Betts. The final trills of the two of them together is one of those things, when first heard, that sound impossible.

All in all, the sound of collectivity head here as throughout drives home a point that I’ve made elsewhere, with regards to utopia and improvisation. Improvised music, in all of its forms -rock, jazz, bluegrass and so on - is immune to reaction of all kinds. It is inherently generative, perhaps a more apt descriptor than “prog”. Under a broad configuration that we can see as improv more broadly, we see a meeting of the minds between DJ Premier and Dickey Betts; John Candy and John Coltrane; Mike Leigh and Bob Weir. Indeed, the cinema of Mike Leigh, much of it unscripted and improvised, yet also based around very specific narratives, parametric determinants for said improvisation is perhaps the best comparative point for bands like the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers. If you get confused, as the song goes, listen to the music play. Naked, Secrets and Lies, or “Dark Star”, it is all the same dialectic of making history - but under the condition of one’s choosing. The parametric determinants of cultural production are prefigurative, not at all the same as the nightmares weighing on the minds of the living.

And thus we are back, on side 4, to improvisation. Without having the above-listed tracks as the toppings of the Mountain Jam sandwich. We broke off in the middle of a drum solo, pounding 4/4, polyrhythms subtle, drone-like. For audience members visiting psychedelic places, the Trucks/Jaimoe drum solos serve as a sort of dissociative headspace, the stimulation of instruments having departed. This continues in the concluding quarter hour of “Mountain Jam”, leading into an intense but melodic bass solo from Berry Oakley and, joined by the organ and guitars, a brief but unmistakable interpolation of Jimi Hendrix’s “Third Stone from the Sun”. More type 2 improvisation follows, before ending up in the hymn, “Will the Circle be Unbroken”, its lyrics denoting a sort of Christian-socialist utopia, a big rock candy mountain. Of course (unlike later in their career), they didn’t actually perform the song itself, moving into more space before finally finishing with a few bars back on the Mountain theme.

The Allman Brothers Band continued their journey through the mid seventies, even without Duane Allman, playing some majestic shows. However, in the main, their relevance deteriorated and they had a series of breakups and reunions - only to reunite in a formal sense in 1989, and play for another quarter century. An apt replacement for Duane Allman had finally been found with the brilliant Warren Haynes, himself also a deeply skilled vocalist. Through the 90s, Betts was in and out of the band, still with the demons of drugs and alcohol. Finally, with him gone, the set two guitarist lineup was Haynes and Butch Trucks’ nephew Derek Trucks, the Allman Brothers’ last two guitar lineup was every bit as original and indeed utopian as the old sounds of Dickey and Duane. This is not to mention the brilliant bass guitarist and singer Oteil Burbridge, who had been a part of one of the great cult improv bands of all time, Colonel Bruce Hampton’s Aquarium Rescue Unit.

For fans of the Grateful Dead, there is a division between those who can’t separate the songs from the specificity of Jerry Garcia being the lead guitarist. Then there are those that believe in the songs. I count myself among the latter- sure Jerry wrote most of them and he was unreplaceable. But I must admit that I saw better Grateful Dead music with the Phil Lesh quintet in the early 2000s than most of the Grateful Dead shows I saw in the fading years of the mid 90s. The current iteration, Dead and Company has made the songs fill the air for a generation of fans who may not have been alive in August 1995 when Garcia passed away. The Allman Brothers legacy, playing until 2014 is indicative of the latter approach. Sure, Duane Allman and Dickey Betts were the pioneers, but they walked so Derek Trucks and Warren Haynes could run. Same with the late Berry Oakley, feeding into the late Allen Woody, the 90s bass player, and finally Oteil Burbridge.

Burbridge is a member of Dead and Company now, the current excellent iteration of post-Grateful Dead bands, no longer touring but expected to play another residence at Las Vegas’s Sphere. a vivid performer, often wearing face paint and elaborate Genesis-era Peter Gabriel-type hippy apparel. One is tempted to make the claim that the prog-rock, psychedelic mushroom spirit of the Allman Brothers is a hidden ingredient as to what Burbridge provides to Dead and Company on the level of aesthetics. Along with the recently minted Dead and Company member (and longtime Bob Weir collaborator), former prog-funk Primus drummer Jay Lane also brings that prog nimbleness. Quite different from the hyper-serious and very far-out improvisation of the Phil Lesh quintet (featuring Warren Haynes), Dead and Company evoke the stadium aesthetic of late 80s Dead.

Of course there will be more elsewhere on the Grateful Dead, notably including their record that often was played side by side with “Eat a Peach”, the live “Europe ‘72”. The point being here, is to examine, in particular, the pioneering work of the Allman Brothers Band in its own right, and how the prog aesthetic they consciously pioneered - in spite of being labelled “southern rock” - actually informed the Grateful Dead family of bands in the long run. Yet as Fred Engels loved to say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. It is my hope, as with everything written in these pages, that readers will develop and enhance their “way of hearing” and listen to this album once again (preferably not on Spotify, but its there!) or for the first time. Prior to Eat a Peach, nothing had ever come close to it, insofar as it being a hybrid of live and studio record that creates a post-festum narrative on the departure of a martyred slide guitarist. Nothing quite like it has ever been issued. Go listen to it!!

![Allman Brothers Band, The - Eat a Peach [Vinyl LP record] - Amazon.com Music Allman Brothers Band, The - Eat a Peach [Vinyl LP record] - Amazon.com Music](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0UIx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F71756057-980d-45e4-add8-f80e8a2cb608_1000x750.jpeg)