Entry Eight - A Consummated Encounter: If I Could Only Remember My Name, by David Crosby

only a child laughing in the sun

As a cultural theorist and historian, my main subject of expertise are the various intersections between music subcultures/counterculture and radical left-wing or revolutionary politics. The frame of my 2017 doctoral dissertation and a number of other things I’ve written on the matter is that there was what I call a Missed Encounter between the New Left, understood broadly, and the cultural left, so to speak, the counterculture. It was not that there were no attempts but there was often a dialogue of the deaf and a sense of mistrust and instrumentalization: even while cultural producers held radical politics, they often either felt above or didn’t trust the organized left. In turn, the organized (white) left often were not really “of” the counterculture(s), seeing them as spaces within which to recruit while not imagining themselves as genuinely part of the community.

The real misunderstanding often had to do, in the last instance, with the mixed consciousness of the cultural producers. Yet could it really be any other way? This was an era in which on one hand, there was a ‘retreat from class’, not so much practically but in terms of who was seen as agential by even some of the most innovative currents in the English speaking left. In turn, significant parts of the labour movement and social democracy were enmeshed with Cold War liberalism. Yet it is more complicated than that, of course. On one hand, Simon and Garfunkel were completely aesthetically enmeshed in Cold War liberalism, the beautiful American soul. On the other hand, radical left, antiwar, pro-civil rights and often revolutionary politics were common sense in bastions of the sixties counterculture. When Bob Dylan “went electric” it was seen as a farewell to the Left, but it was more Dylan frustrated with the Stalinist folk music scene. When asked why he stopped writing protest songs, Dylan answered that all of his songs were protest songs. This was most apparent to Huey Newton and other Black Panther cadre who did study groups on “Ballad of a Thin Man” among other 1965/1966 Dylan lyrics.

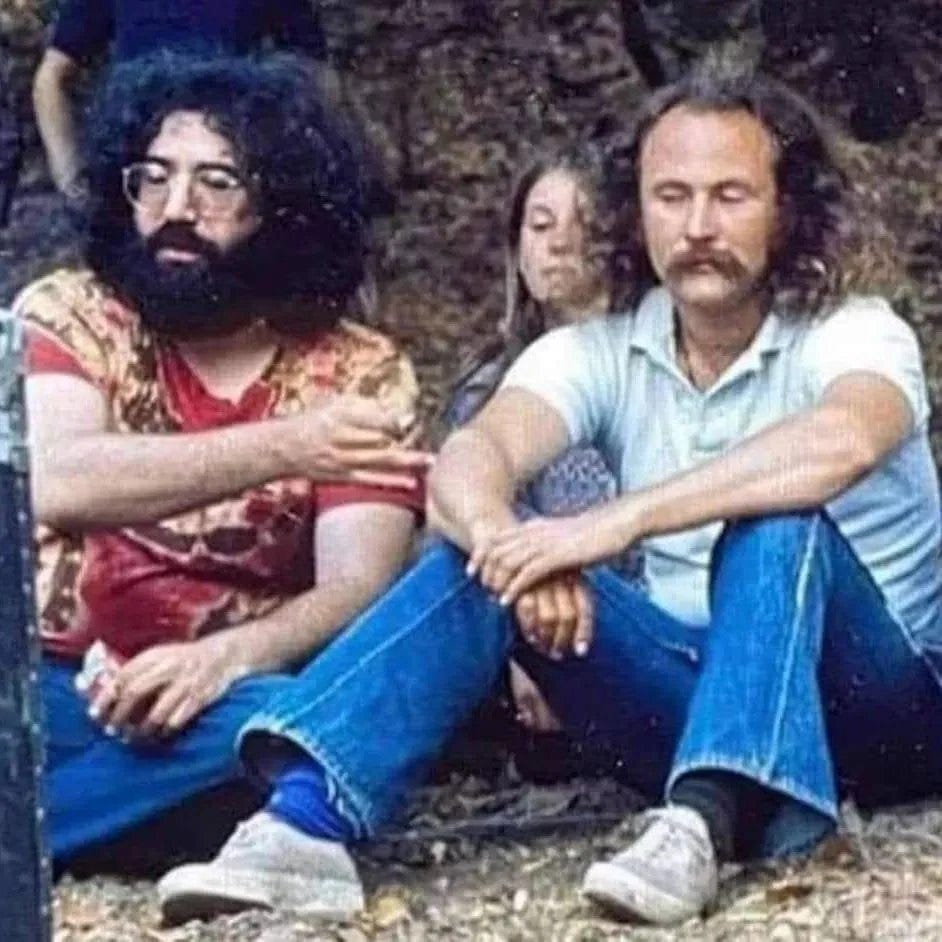

In California in particular, and in particular the San Francisco Bay Area, while they didn’t always get along, the New Left and the counterculture were basically the same scene. That there were practical differences between the spiritually anarchist musicians and Marxist left is not altogether surprising, but they were on the same side in a very real sense. There is much that has yet to be published about the connections, for example between the Grateful Dead, the Black Panther Party and the broader California Left - including the labour movement. Jerry Garcia had a very real bond with Huey Newton. Many of the original “Acid Tests” were held at union halls with the knowledge and often enthusiasm of trade unionists, often longshoremen. Tom Wolfe, a hack who I’ve called an electric kool-aid asshole, makes far too much of the personality, not political differences the Dead had with the Berkeley Left. The Dead and others from the Bay Area will be focuses more particularly for future entries, but for here in particular, a broader and even exemplary, if obscure project of this encounter is our object of analysis.

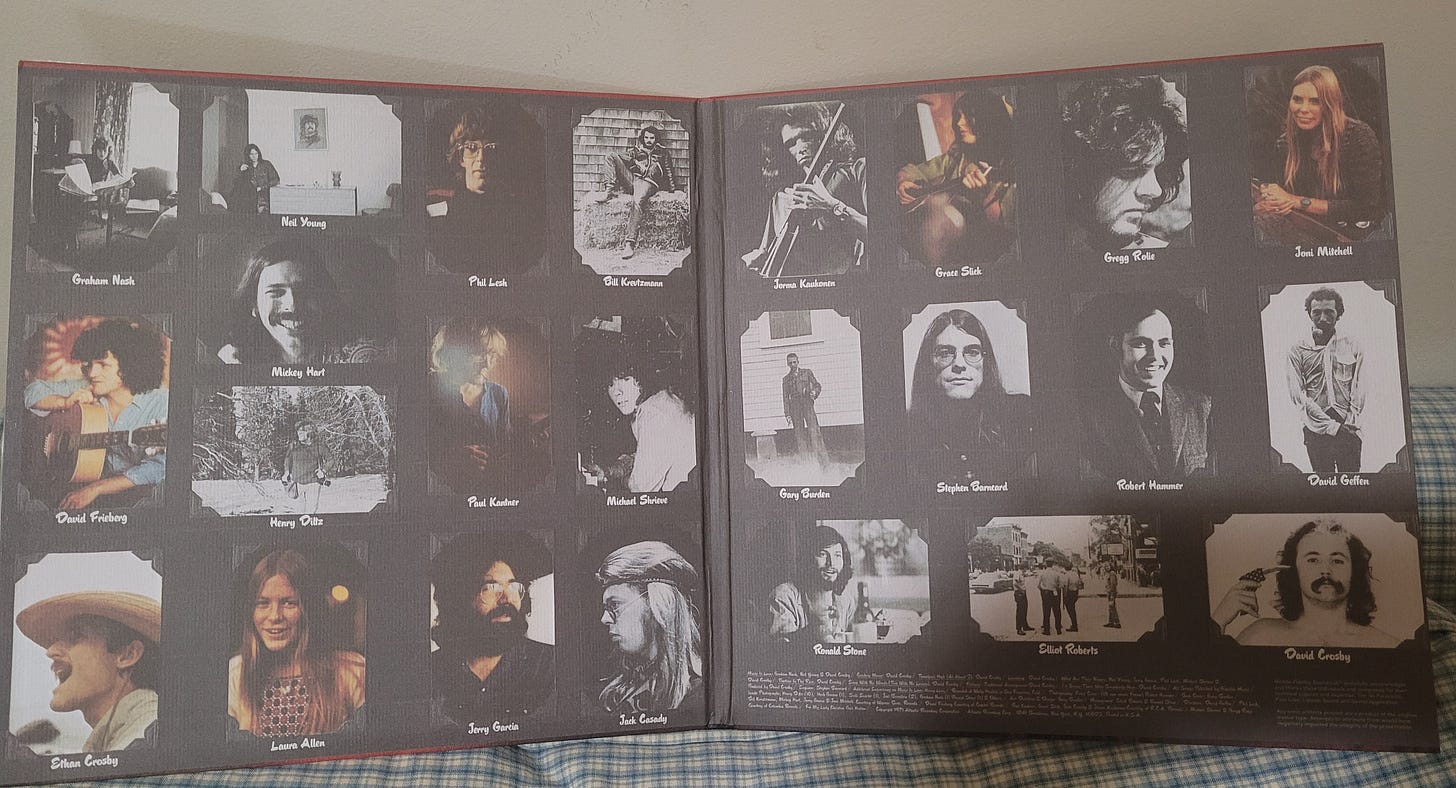

Around the particular period in which parts of the New Left were either moving further left or working within the system, arround the period of 1969 to 1971, there was the advent of the “supergroup” in rock music, the musical equivalent of a multi-tendency organization. This is to say, a group of established musicians/singers/songwriters coming together, sometimes to form a new full fledged career act, and sometimes for a one-off. To a certain degree, this was both a creation of the industry, and, to its more astute A&R men, a chance to eventually cultivate solo artists. By making these artists singular figures, their bands could be secondary. As individual cultural producers moved by the likes of David Geffen and Clive Davis, like chess pieces. Everybody thought David Geffen was a hip capitalist until he sued Neil Young in the eighties for not sounding like himself. In any case, David Crosby was in two of these supergroups. One, of course, was Crosby, Stills, Nash and (sometimes) Young. Yet the superior one of the two was The Planet Earth Rock and Roll Orchestra (PERRRO).

Never putting out an album under their own name, PERRO were nonetheless a staggeringly good studio rock band - and those with their nose to the grindstone should easily be able to attain bootleg recordings. PERRO’s debut was on Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kanter’s “Jefferson Starship” album, the radical-left sci-fi cult classic Blows against the Empire. Of note, this was not the later formed and even later approaching self-parody band Jefferson Starship, rather it was the moniker used by Kantner for this particular record. The initial set of epic jam sessions also produced the pieces of music that constituted both Graham Nash’s quite underrated debut solo record Songs for Beginners, and this one. Fundamentally, however, while Crosby is the lead singer and songwriter, this is not a “solo album’ by a singer/songwriter. This is an album that, with its vast cast of characters, is a crystallization of the very best of the west coast musicianship. It is beyond merely a supergroup, it is the golden chalice of west coast psych rock.

PERRO featured of course David Crosby on rhythm guitar - and in this case lead vocals. With the exception of the drummers, every member of PERRO also sang, with some - notably Neil Young and special guests Graham Nash and Joni Mitchell sharing lead with Crosby on some tracks. Lead guitar duties fell to the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, Neil Young, and Jefferson Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen. The Grateful Dead’s dynamite rhythm section was also on board, with Phil Lesh on bass guitar and the ‘rhythm devils’, Mickey Hart and Billy Kreutzman on drums and percussion. Many more one-offs play keyboards here and autoharp there, and perhaps over a dozen sing on the hippy revolutionary anthem “What Are Their Names”. This particular song expresses a revolutionary sentiment far removed from the "smile on your brother” aesthetic of the Summer of Love. The piece of mind on offer here seems far more aligned with Luigi Mangione than Timothy Leary.

I wonder who they are

The men who really run this land

And I wonder why they run it

With such a thoughtless hand

What are their names and on what streets do they live?

I'd like to ride right over this afternoon and give

Them a piece of my mind about peace for mankind

Peace is not an awful lot to ask

In a sense this reflection of 1970 revolutionary and countercultural sense constitutes a reversal of the famous 1965 speech by SDS leader Paul Potter which exhorted the movement to “name the system”, to understand the social forces that brought about the Vietnam war. By this reductionist stance, this, and lyrics like Crosby’s comrades in Jefferson Airplane’s “We Can Be Together”, this would mark a regression from Potter’s 1965 structural approach back to individualizing “bad guys”. Yet this angry but stoic hippy revolutionary song is much more in the tradition of classic union folk songs, that could be generalizable, in the sense of “Which side are you on”, but also could be specific in the same lyric. In other words, a generalizable message could also be very individualizing, in particular sending a veiled warning of “piece of mind” towards potential scabs and “thugs for J.H. Blair”. The lyric for “What are their Names” is at once conciliatory, using the same neutral and pacifist “peace” discourse” as in the “summer of love”. Yet in this sense, “peace” not being a lot to ask is being articulated in concrete solidarity with Anti-Imperialist struggle in Vietnam.

"What are their Names” is the most explicit “protest” song on this record but not merely in the sense of its lyrics, which come in nearly 2 and a half minutes into the song, pretty much as a coda. The bulk of song is an intricate instrumental, starting with guitars weaving around each other, with gradual introduction, both in content and in volume, of bass guitar and drums. Neil Young and Jerry Garcia play lead guitar, along with Crosby’s steady and quite underrated rhythm playing and Phil Lesh playing bass guitar. If one were to cross “Dark Star” with “Down by the River” and add the song structure of “Wooden Ships”, you’d get the minor key and mournful guitar elegy. This is not some dilletante session of Derek and the Dominoes, it is much more akin to Charles Mingus’s “Fable of Faubus” It is quite likely that the improvisation itself was recorded during those epic PERRO jams in the summer of 1970, and found its way into a song. And indeed a lot of the album are clearly songs written around PERRO improvisations.

Another notable PERRO jam on the album is “Cowboy Movie”, a song that also elliptically refers to the break-up of Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young in the immediate aftermath of the hit album Deja Vu. The lyrics are somewhat secondary, and sometimes a bit cringe but nevertheless fun in an historically specific way. Behind the western movie metaphors, it is bros getting mad at bros. To Crosby and friends, Stephen Stills was “not like us”. Crosby and Young stuck with Nash, who seemingly had his partner taken by the womanizing Stills, known to love the one he’s with. The real story of this over 8 minute song are not the throwaway lyrics, but yet another example of lead guitar pyrotechnics from Young and Garcia, over a groove that is only a slight remove from “Down by the River”. One would be tempted to point out that Stills and Young had often performed guitar duels on said track going back to the origin of CSNY, and now Young had an upgrade. But that would probably be applying too much intentionality to the operation.

With the jams on one hand, the other type of song on the album is a mix of virtuoso playing and harmonies in the spirit of what Crosby had already done, with CSNY but without the smarminess of Stills, and, frankly, with a better band. The record’s opening track “Music is Love” is quite literally a Crosby, Nash, and Young song, with all three of them sharing the lead as well as harmonizing, and with both Crosby and Young’s unmistakable guitar style. Added to this are subtle percussion sprinklings from none other than Young, playing vibraphone and congas, foreshadowing some of his later ‘deep cuts’, notably “Will to Love”. “Traction in the Rain” has a similar vibe, with more instrumentation, the overlapping unison acoustic guitar sound that Young later put to use on his Comes a Time LP, with even Garcia joining in, albeit somewhat incognito.

“Tamalpais High” and “Song with No Words” both, literally, have no lyrics, just classic Crosby/Nash harmonies and mellow, ambling grooves. Garcia and Young are in both of these cases joined by Jefferson Airplane’s Jorma Kaukonen on guitar. Finally, perhaps the most famous track on the LP, the one that came close to being a “hit” was “Laughing”. An absolute classic, it was originally performed by groups variously presented as “David and the Dorks” or “Jerry Garcia and friends” in the fall and winter of 1970/71, AKA the Grateful Dead with David Crosby. Having heard some of these versions, with their guitar pyrotechnics and Crosby’s very emotive live vocals, I can nevertheless say that the studio version, with Crosby harmonizing with Joni Mitchell and Graham Nash takes the cake. Of course this is helped by backing from the house band, the Grateful Dead’s rhythm section and Garcia, and an arrangement and production that immediately evoke that period of American life in which there was still mass faith in profound social transformation.

Crosby’s short lyric to “Laughing” riff off of his rejection of sixties spirituality, one of “the man’s” major forces of counterinsurgency. Writing of meeting a man (George Harrison) who introduced him to the fraud and sexual predator that was Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his transcendental meditation scam. Yet the subject matter of being caught up in some hippy spirituality as opposed to attempting to find out “what are their names” is even generalizable to the entire mythmaking apparatus of the time, including “the star maker machinery behind the popular song”. All things being equal, and backed up by the aural equivalent of recognition of contradiction, Crosby reveals himself as mistaken, a child laughing in the sun. Recognition that the truth can’t be found by otherworldly revelation, and instead, by way of attempting to shift reality itself can only but provoke laughter.

If I Could Only Remember My Name is part of a cluster of records in which we are presented with the exception to the general historical rule, a consummated encounter. Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers, with its explicit references to “forces of chaos and anarchy” and the expropriation of private property is a key part of this constellation. So is the expression of the Black radical tradition that is Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On. On the other hand, so are more elliptically and culturally radical records like the Grateful Dead’s American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead; The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo; Neil Young’s After the Goldrush, the aforementioned Jefferson Starship project, among many others. Most, if not all of these records are rooted in California, primarily the Bay Area. This constellation of music will continue to be engaged here, and is indeed not unrelated to some of what has already been addressed. All of this constitutes part of the chaos of memories of what could have been and perhaps briefly was a new cultural front. It is time to start reconsidering, and always, keep laughing.