Entry Four - Welcome to the Machinery: On Joni Mitchell's Court and Spark

Hey, where you going? Don't go yet! Your glass ain't empty and we just met!

The early-to-mid seventies was the dawn of the era of the singer-songwriter. On one hand, the music industry was very interested in solo artists. In this case, their session musicians could be paid union scale (nothing to sneeze at), and in turn, this allowed for a great many existing solo artists, veterans and newbies alike, to thrive. Of course, then, there were the mediocrities. It was all about “stoking the star maker machinery behind the popular song". This is all to say that abstractly speaking, for example, I ‘get’ James Taylor. I even sort of like a few of his songs. Jim Croce is beloved by many. Neil Diamond is a journeyman, without a doubt. But there is some justification that the singer/songwriter craze of the period does not encompass its greats, like Warren Zevon, Jackson Browne, and indeed Mitchell. But to simply make the claim that these three ‘transcended the form’ is to buy into the idea that there was a unified form in the first place, beyond the star maker machinery.

At the same time, what this era produced was a sort of prototypical post-New Left cool, a “mellow” attitude towards the world. The late Neil Davidson and I used to talk about how Steely Dan, a favorite of both of ours, was a signifier of the defeat of the Left and the rise of neoliberalism. If the Dan were the tip of the spear of the sort of enjoying-the-ride capitalist realism, the “gentle and soft” was there for a reason. In turn, beyond the deceptively ‘soft’ form of appearance of records like Blue, The Royal Scam, Court and Spark, Aja, is a utopian core, in the Jamesonian sense. Art that engaged in immanent critique of the plasticity of what became known as the “me decade” was not mere negation. To engage one of Mitchell’s earlier songs, there was still a route “back to the garden”. It just may be more circuitous. It had to squarely see what horrors were now upon the world, and in particular, what was happening to these self-contained networks of musicians themselves.

As Robert Christgau wrote about Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark, “the relative smoothness is a respite rather than a copout”. Indeed, the polysemic quality of ‘smooth’, to paraphrase This is Spinal Tap, meant there could be a fine line between being out there and cringe. Take Steely Dan’s “Hey Nineteen”, from Gaucho, or Mitchell’s cover of Annie Ross’s “Stranded” which manages to be avant garde and traditional simultaneously. Both songs exhibit time out of mind, a New Left sensibility confronting the me decade. With this in mind, Christgau’s notion of a respite was one from defeat. The late sixties had seen a wave of hope, that the revolution or some form of profound social transformation was around the corner, that the vibe of the era was irresistible.

This was the sixties zeitgeist that united the New Left with the music/countercultural scene. This great wave, as Hunter S. Thompson famously put it in the great and misunderstood dystopia, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, the wave “broke, and finally rolled back”. In response to this defeat, while some previously prominent elements of the organized left trended either ultra-left or “working inside the system”, cultural production looked inward. Prefigured by the reactionaries shooting the hippy bikers in Easy Rider, we start to see, in music, cinema, and television a sense of mixed up confusion. In 1968, a young Dustin Hoffman falls in with a cougar, as it were, in the classic, The Graduate, set to the Cold War social democratic pop rock of Simon and Garfunkel. Now the liberal Hoffman is replaced by a man who goes to extreme and murderous lengths to literally defend his property, in Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs.

This confusion is also what marks the brilliance of the best work of singer songwriters of this particular era, those who had walked so others were running. The respite that is Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark needs to be seen as part of a configuration of records that includes, if not his whole ditch trilogy, Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night, Leonard Cohen’s New Skin for the Old Ceremony, Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, artists already veterans in their mid thirties. Cohen asks reflectively what all are asking implicitly, “Is this what you wanted?” These albums range from playful in the case of the Canadian Cohen and Mitchell to dark and even unhinged in the case of Dylan and Young, but they are all of a piece (and all will be addressed in whole or parts in these pages).

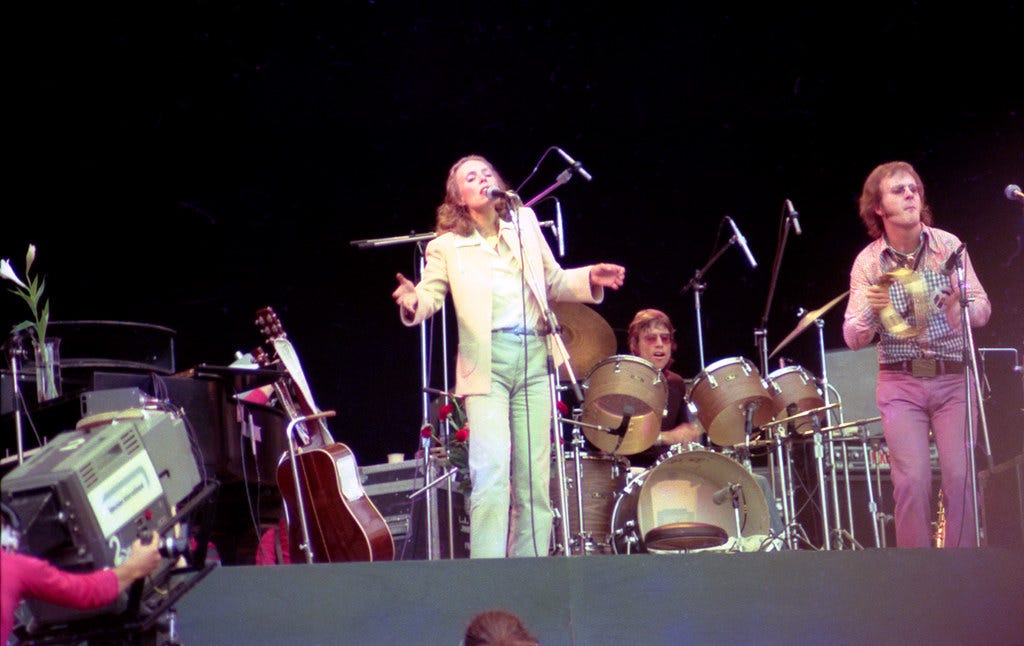

A wide range of artists in the 90s and 2000s, notably hip hop artists like Tribe Called Quest spoke about the sonic influence of this album, and Mitchell’s - sound - at the time. And this is they key point to Court and Spark being if not the best, but the highlight of her great four-album run of masterpieces at the time. While she would continue to put out adventurous music - and as is shown recently, her career is far from over, nothing she did ever achieved the almost platonic ideal of a sort of sharp and mellow vintage. This is an album that could show vulnerability but also party with Cheech and Chong, albeit not without confusion over what to do at parties at any rate. The topicality, the down-to-earth and more descriptive, less impressionistic lyrics, however, could not have been pulled off without how this album sounds.

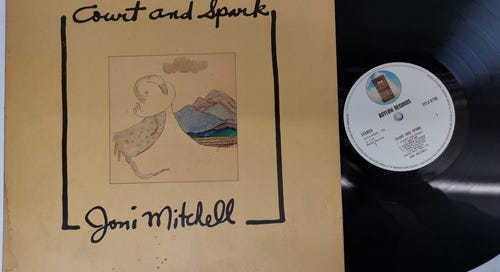

When I want to see how a turntable sounds, this is one of the first albums I go to. There are very few recorded parcels of sound comparable to this ‘soundstage’, that is to say the syn-aesthetic space in which the instruments dance in fixed space demarcated by the left and right speaker on a stereo recording. The prominence of keyboards and woodwinds comes at the listener right from the middle and somewhat higher than the listener. Drums occupy the same geographic space but lower down, as if to be a supportive floor for the supremacy of the woodwind. Acoustic guitars are subtly on the left, and even to their left is bass guitar and various percussive elements, with again the percussion acting as a support for the melodic instrumentation. To the right are electric guitars, sometimes more than one, with a subtle floor if more percussion and the odd sound like a tack piano or perhaps a faint flute. Then there’s Mitchell occupying a space in the centre between the drums and the keyboards and woodwinds, but also range and panning from the left to the right and back.

Mitchell’s voice is at once powerful but very specific to the cultural product itself, and more to the point, as being a part of a band. On this album more than any other of her career, save the live record Miles of Aisles, does Mitchell, albeit without any sacrifice of her persona, is a band member, with her voice acting as much as an accompaniment for the woodwind and guitar as they are to her voice. It is just that her voice is what guides everything else. The extension of a vowel is emulated by a guitar solo as much as a woodwind trill is facsimiled as the aforementioned vowel extension, as on “Raised on Robbery”.

The instrumentation, in the main, is a prefiguration of the greatest work of Steely Dan. This is not surprising given that Larry Carlton, iconic in particular for his playing on their “Kid Charlemagne” is the primary electric guitarist here, though there are appearances from Fellow Ontarian Robbie Robertson and the enigmatic Jose Feliciano. Others on whole or part of the album, notably Carlton’s colleagues in LA Express, a jazz funk band who had also done the famous soundtrack to the quasi-pornographic animated film The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat. Most notable here, and taking a leading role in the album’s sound, while never been ostentatious, are the woodwinds of Tom Scott. This combined with another LA Express member Joe Sample’s keyboards is what more than anything sets the palate.

Perhaps the most representative here of this transition of the old folkie Mitchell dying and the new jazz Mitchell just being born is “Raised on Robbery”. It is deceptively more accessible than earlier Mitchell songs, with regards to lyrics, yet this itself, to recall Christgau acts as a strength. Even on a purely poetic level it allows for ellipses and poignancy and humor. We are presented with a man stressfully watching a hockey game at the hotel bar, he has money on the Maple Leafs, then as now, perhaps an unwise bet. A sex worker sees him as a potential client or perhaps friend, and takes a bit of a liking to him, info-dumping a little bit. Using somewhat ingenious culinary cryptical envelopment, she describes the struggles of life. She’s a “pretty good cook”, without a doubt, but times are tough, she has to cook even after midnight. She’s tough, she’s been around, she was raised on robbery in the sense that she’s had to survive a strange transitional time, not unlike the period in which this work was produced. And yet she is disappointed and seemingly genuinely hurt when the man leaves before anything takes place besides having someone to talk to while sharing that drink that’s called loneliness, better than drinking alone.

This is all set to an arrangement that starts with a vocal overture and then moves into a sort of ramshackle funk-boogie. Robbie Robertson snakes in with a razor-sharp lead guitar part. It’s a catchy song and a banger, danceable, checks off all the columns. One also is encouraged to visit an alternate version, performed with Neil Young and the Santa Monica Flyers. And the real achievement of it is that it is not that it is surrounded in is equals. There’s the mysterious textures of the opening title track, the hit single, “Help Me,” notably referenced by Prince on "The Ballad of Dorothy Parker". “People’s Parties”, whose title may be a pun on political parties, is a song about the emergent subjectivity of he mid seventies, “coming to people's parties, fumbling, deaf, dumb, and blind”, and in turn, the overall purpose of this empty socialization is to “keep the sadness at bay”.

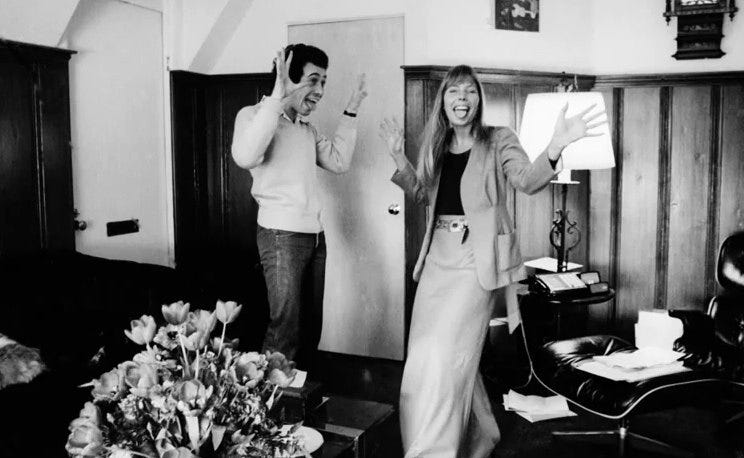

As a work of cultural history, what is perhaps the most notable song here is “Free Man in Paris”. A woodwind intro that sounds like it could be the theme for some obscure mid afternoon CBC radio program and crisp guitar from Jose Feliciano brings us into one of the best songs ever written about the emergent rock music industry. Indeed, as a scholar of the period, I structured an entire chapter of my doctoral dissertation around the lyrics ot this song. The title character here, the “free man” is Joni’s close friend David Geffen, a fascinating historical figure, a tastemaker par excellence, from Jackson Browne and Warren Zevon to Kurt Cobain and Gucci Mane. Then of course there’s Dreamworks, insider trading and spending the early days of the Covid 19 pandemic on his yacht once owned by a Russian oligarch.

Geffen and Mitchell took a trip to Paris with Robbie Robertson and his partner, and it brought out a wistful side in Geffen, at time an A&R man at Atlantic Records, though someone who would soon branch out. Geffen is of the first generation of what is now archetypal, the hipster capitalist, whose knowledge and genuine respect and love for the music industry and his friends, the musicians, is no match for the mute compulsion of capital. He is indeed largely responsible for keeping alive the careers of many artists who didn’t sell a lot of records, though this didn’t come without him suing Neil Young for not sounding like himself, in the eighties. But here, back in Paris, Geffen tells his friend Mitchell how he feels, like a free man, unfettered and alive. Of course, he would just stay if it were up to him but he’s become a personification of capital, what was once loose affiliations of local promoters, hippies and the odd gangster, had become “the star maker machinery behind the popular song.”

People weren’t in it for the right reasons, as those hipster capitalists of Geffen and Bill Graham and Clive Davis’s generation would say. They were just “trying to get ahead” and given his own success, to Geffen (as told to Mitchell), they were trying to be his friends. Later venting, including elliptical complaints about feeling forced at the time to be closeted. In the second verse, the refrain about a good friend is reframed. At first good friend is a reference to someone who wants to suck up to Geffen in the industry. But here, this is longing to find a lover, “down the Champs-Élysée, going café to cabaret”.

What Mitchell achieves here, and this infuses the rest of this record, is to sit at a moment of historical significance for popular music and be able to chronicle it as a cultural product coming right out of the industry under analysis. The empathy in her vocal performance is that to think she was singing right to Geffen, and perhaps sadly seeing how it would all turn out. This was, to use Marxist language, the full subsumption of a given form of cultural production, while still regionally mediated, still surrounded primarily by emergent multinational corporations. The cultural industry in general consciously attempted to be recuperative, famously with Elektra records having inside record sleeves proclaiming that the “Man” can’t keep music down. And those who had come up in the regionalized and often implicitly worker-managed music scenes, those on the facilitative end of things like Geffen, were thrust into a new position. He was no longer subject to the moral economy and the customs of regionalized and countercultural “scenes”. He was now an object of market compulsion, and his pal Joni feels a sense of compassion, perhaps knowing, perhaps not knowing how he would end up.

Court and Spark comes at the tail end of one of her periods of greatness, and at an entry point into an increasingly jazz oriented aesthetic - most notable in her collaboration with Charles Mingus. Yet, if I am being honest about what I take to be Mitchell’s greatest artistic achievements, it was from this period in which she had moved beyond the painted ponies going up and down but had not yet entered a new period of experimentation. Like Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, it manages to be both the most accessible and most artistically successful album of her career. Like Leonard Cohen’s The Future, she is solidifying a new sonic palate. This is just a perfect piece of popular music. It is a wistful goodbye the sixties and regional music scenes, and a deceptively foreboding description of the dystopian machinery below the surface.