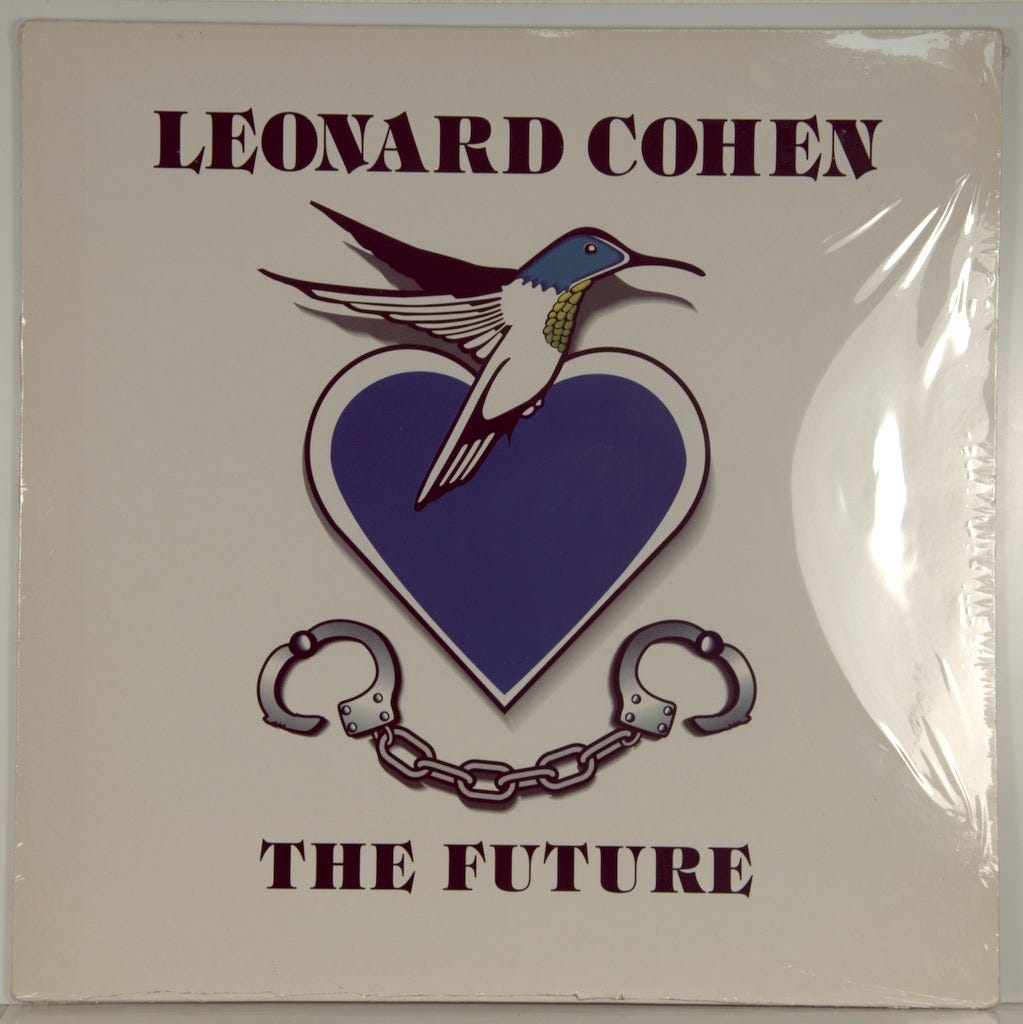

Entry Seven- Eschatology with a raised eyebrow: The Future, by Leonard Cohen

The Little Jew who wrote the Bible

To my readers, my sincere apology for the delay on this particular entry. I am aiming at two-three entries a week, but sometimes life happens. Please do keep reading, and share with a friend!!

Being a union member who has been on strike four times, I’ve heard “Solidarity Forever” more times than I can remember. More to the point, I’ve heard it bellowed by all too many union bureaucrats. Their “Solidarity Forever” is really, as a large group of members of my union once joked, is really “solidarity for a while”. Indeed, on one drunken evening during one strike, a large group of fellow workers and myself, enough to fill as many tables at a pub that there are verses in the song. Each table collaborated to write a new verse about bureaucratic tendencies on our union’s bargaining team at the time (2008/2009, for those wondering). These tendencies, and petty infighting led them to drop key demands for the bargaining unit classified of graduate student workers classified as ‘graduate assistants’ by our employer, York University. So each verse ended with “until they sell out Unit 3”. I still have the lyrics. I think they went out over the old “Strike to Win” list-serve with some references to “right wing social democrats” or some such.

Yet no matter how much the song has become meaningless given its bureaucratic appropriation, there is one version of “Solidarity Forever” that never fails to move me. This version, by the late poet, novelist, songwriter and “great Canadian” Leonard Cohen, distills the song right down to its essence, not of bureaucrats, staffers, and elected union officers. Reordering the lyrics and, like most, extricating two little performed verses, Cohen begins with the last two verses. The song thus starts with reference to how capital has taken untold millions, yet without our brain and muscle, “not a single wheel would turn”. The narrative of the song, performed slowly and deliberately on an upright piano is reframed. Giving birth to a new world from the ashes of the old can only come with awareness of one’s enemy. The first two verses are then performed in reverse order, thus the final line before the final chorus, “yet what force on earth is weaker than the feeble strength of one, but the union makes us strong.”

It is not a rousing anthem in this case. It is performed in a sense to really encourage the audience, seemingly, to understand the gravity of what they were up against. This is more like another one of his covers, the French resistance song “The Partisan” in which the struggle is clear, rather than a conference centre banquet room full of bureaucrats in bad suits. Cohen starkly lays out the darkness, but also the “crack in everything where the light comes in”, that is to say, the new world from the ashes of the old. Trained at a young age from socialist camp counsellors as to the power of song, Cohen was a past master, a “Kohen”. And of course, on The Future, Cohen seems to be making an attempt to lay out that new world, but not without staring starkly at the future. And of course, there is some humor, some fun and some, well, real emotion.

As opposed to covering a song from the anti-fascist and socialist tradition as had past been his custom, Cohen covers an obscure soul-jazz song, “Be for Real”, originally performed by Marlena Shaw and written by journeyman songwriter Frederick Knight. Cohen ends his recording, which is both schmaltzy and passionate and indeed quite sweet by thanking “Mr. Knight” for the song. What is more, Cohen also expertly covers Irving Berlin’s jazz standard “Always”, letting his band and synthesizers vamp for 8 minutes, and with his deepened voice, acting as a legitimate jazz crooner. These two cover songs, adornments showing that Cohen has nothing left to prove except perhaps his increasingly impressive phrasing. More to the point, however, is how both songs, of commitment, of love, of solidarity, drive home the narrative of the record.

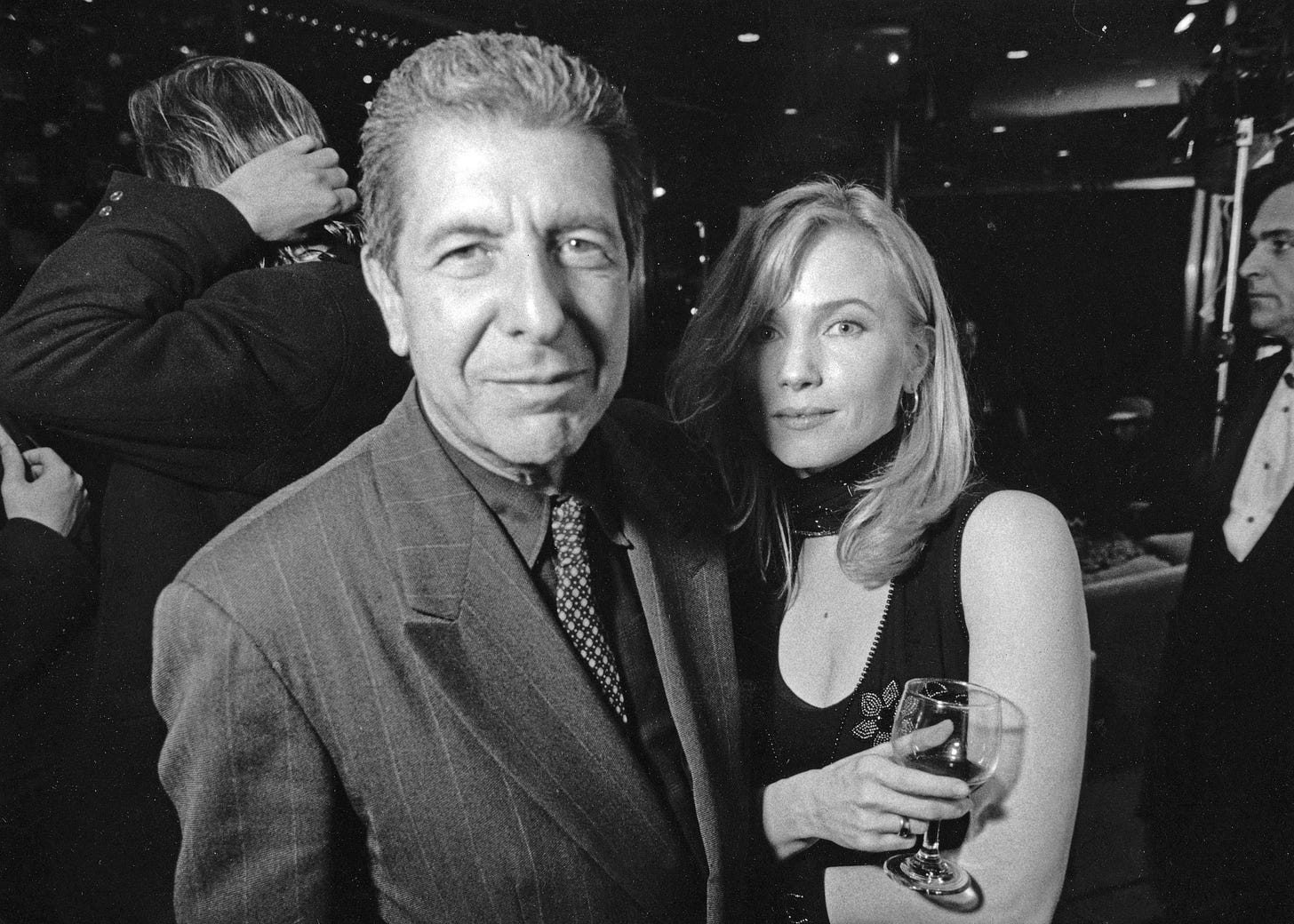

The Future is an album about solidarity forever, including that solidarity between lovers, as Cohen at the time had found with actor Rebecca DeMornay, who cowrote some songs. Yet it is a solidarity presented in a cryptic and dialectically complex idiom. As with his previous album, I’m Your Man, and perhaps even moreso, Cohen’s songs were entirely built around synthesizers and drum machines. And what’s more, some songs, notably the title track, seem based on a synthesizer’s pre-set pattern with a minor variation or two. This is not as uncommon as one may believe, as is best exemplified with Gorillaz song “Clint Eastwood”. This is not just the aesthetic of when the albums were recorded as he doesn’t deploy synths like, say, Tears for Fears, INXS or Pet Shop Boys. Rather, this evokes earlier experimental synth based music, notably Suicide and Japan. This is not to mention Cohen’s album ending, six minute plus instrumental, the mysteriously named “Tacoma Trailer”, which serves as a repetitive, ambient/classical/synth coda, closing credit music to help one wash down the profundity of what one has just heard.

The Future as narrative pivots around four specific songs: the title track, “Waiting for a Miracle”, “Anthem”, and “Democracy”. The former two open the record, while the latter two mark the halfway point. The former two are perhaps about the quite fear-inducing reality that Cohen is attempting to articulate, the ashes of the old much more than the new world. The new world is addressed, in turn, circuitously and even ambiguously on the latter two. In a simple sense, upon which I will expand, “The Future”, the title song is somewhat akin and perhaps informed lyrically by the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil”, yet the narrator is not Satan in a Christian sense, as Cohen is steeped in Jewish, Gnostic, and Buddhist theology. Rather, the narrator here, like on “Waiting for a Miracle” seems to be Cohen himself occupying the role of gnostic demiurge. Conversely, the narrator of “Anthem” and “Democracy” is Cohen recasting himself in a more classic prophetic sense, yet with the same sardonic anxiety found in the first two tracks. To delve deeper into the politics of these four songs, and thus the record itself, it is worth engaging some of the existing work on it, in addition to how it has been deployed in popular culture, perhaps most famously in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers.

In a superb, if somewhat selective analysis of Cohen’s work in the indispensable Canadian leftist online journal The Breach, academic Aaron Giovannone refers to Cohen as a “Cold War Troubadour”. The point being not that Cohen was a cold warrior but that he, and the Canadian state that deployed him as a cultural ambassador of sorts, fancied himself as above the US/Soviet binary. Indeed this binary kept the world safe, it brought equilibrium, in Giovannone’s reading of Cohen. And thus Cohen suddenly became explicitly political in the late Cold War period on his I’m Your Man LP. But then, one wonders, who are the good guys that lost the war that supposedly “Everybody Knows” about? Giovannone surprisingly thinks this is a reference to the Cold War, when it was written well before the Cold War had formally ended. The war that Cohen is referencing, if one has to be literal about it, is obviously the class war. Given the other references, it is more likely to be a song that can be taken, rather, as Cohen pointing out that everyone knows that the system is completely fucked up, so to speak. The problem is that they don’t know what to do about it. Thus, the poet, “whose job is to shed light, but not to master”, is here to inspire, but not to instruct, about finding a new world in which it is no longer the case that the fight is fixed, the poor stay poor, and the rich stay rich.

Giovannone is however quite astute with regards to this record, seeing it as a response to the dominant Cold War triumphalism. Yet this response is rooted in his somewhat far fetched analysis mentioned above, of Cohen, reflecting a not uncommon view within the Canadian liberal intelligentsia, saw the Cold War as bringing stability and equilibrium. The record is indeed a response to Cold War triumphalism, to my mind, but it also is a clearing of the deck that goes back to the beginning of the Cold War itself. The narrator of “Waiting for the Miracle” has not been so happy since the end of the second world war - a time before what most historians think of as the Cold War. Against the backdrop of perhaps the most goth melody and synth palette of his career, the song continues its predecessor (and “Everybody Knows”’) tone, but beyond making manifest of the horrors of the world, it is about the boredom that comes after a war that has been constitutive of human existence. There is also reason to believe there may be a link with the similarly titled song “Waiting for a Miracle” by Cohen’s friend and colleague, Bruce Cockburn, famously covered by the Jerry Garcia Band. It is a traditional protest song about the fighting spirit of the oppressed, and perhaps this is simply Cohen’s take on that.

The take itself flows out, however, of the album’s manifesto of a title track. And this is how we can situate Cohen’s ability to crystalize what could be seen beneath the surface, against the New World Order proclaimed by George H.W. Bush aligned with Gorbachev and even the gladly fallen Assad dynasty. Against the “end of history”. Cohen is akin to Walter Benjamin’s theorization of the angel of history. The angel is about to look away from something but he can’t help but stare. There is no history except the history of defeat, in both heavenly and earthly realms, class struggles in all the vicissitudes. But what had been broken could be made whole, the new world from the ashes of the old. Yet, the angel, like the enigmatic dove on the album cover is in a strange situation. “The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

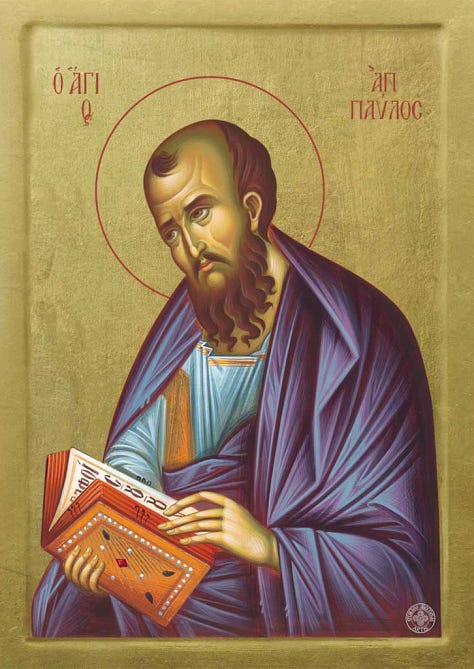

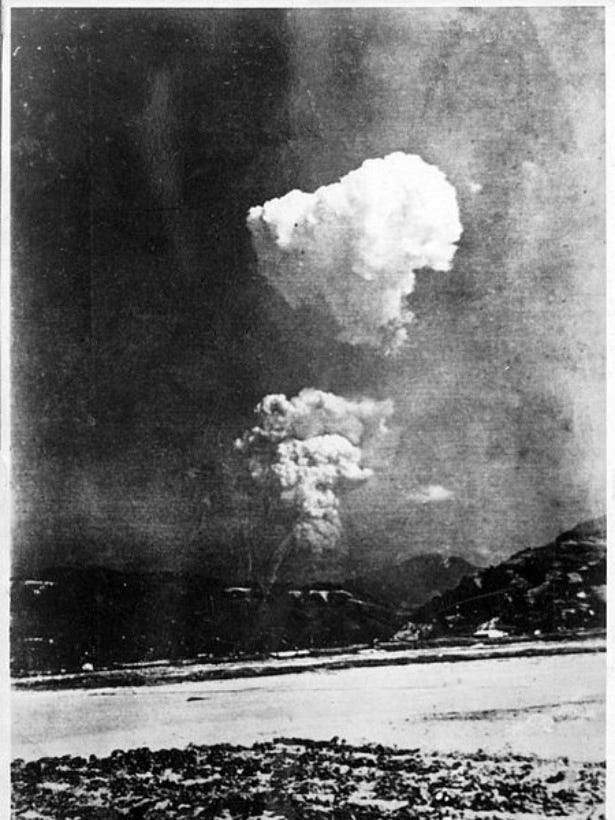

Cohen the prophet and the sacrificial priest has a distinct and somewhat Brechtian or archetypal modality here, as noted, informed by “Sympathy for the Devil”, seemingly. “The Future” is murder, if we allow it to be murder, and the narrator doesn’t really have too many fucks to give. There isn’t even an original melody necessary here, just seemingly chord changes on a pre-set synth pattern. The narrator through historical figures and events that, however terrible or world transforming, or both, could at least be understood. The Berlin Wall, Stalin, St. Paul, later adding Christ and Hiroshima. “The blizzard of the world”, like Benjamin’s storm, has fundamentally trapped or shifted the human soul, thus what was what to repent about, and to whom? If Mick Jagger was attempting to channel the spirit of ‘68 by telling his audience to call him Lucifer, Cohen is the “little Jew who wrote the bible”, the teller of tall tales and appropriator of the role of how Christian hegemony understands “God”. And this little Jew has a sharp, even somewhat childish sense of humor, with the odd double entendre, “Give me crack and anal sex… Take the only tree that's left… And stuff it up the hole…In your culture”.

If these first two tracks were the manifesto, it is with “Anthem” and “Democracy” that the narrative comes together, along with its accompanying songs. Significantly, on the vinyl version of the album, the former song closes side A, while the latter opens side B. I vividly remember how often I would hear the chorus of “Anthem” quoted in the 90s in leftwing spaces. I believe what I - and we- took from the lyrics - that sweet image of light finding a crack in the darkness, oh so polysemic, yet in context, seemingly at the very least generalizable to the struggle of the oppressed and the class struggles. The effervescence of the enthusiasm toward a political opening is irresistible. “Ring the bells that still can ring - Forget your perfect offering - There is a crack a crack in everything -That's how the light gets in.”

Said Bells, like Dylan’s “Chimes of Freedom”, were both material, as in the various sounds of effusions one hears in the sense of the possibility of freedom being introduced. The “perfect offering” could well be a very personal reference, by Cohen, to his lineage as a Kohen. Priestly Judaism was pretty much entirely replaced by rabbinical Judaism after the destruction of the second temple, and one of the acts of the high priests, the Kohanim, was a sacrificial offering. The Jewish high priests - as opposed to rabbis, normally came from a specific bloodline, as opposed to Rabbis who were simply religious scholars ministering to local synagogues. The Kohanim, or high priests, “the little Jews who wrote the bible”, as it were, were in charge of the Ark of the Covenant. More significantly to Cohen, as to Gershom Scholem, is that their theology, unlike that later developed in Rabbinic Judaism and in the latter part of what has come to be known as the Pentateuch, is the lack of literalism. There are no angels or spirits writing the bible or doing anything else. That was seen by the priests, and especially the high priests as Zoroastrian and later Christian corruption of Judaic theology.

Yet this anointed offering is insufficient in the context of the capital f Future. The ringing of the bells that prompts the crack appearing is a rupture, a break with priestly and fatalistic teleology. Wars will be fought, settled and fought again, until this rupture takes place. But then this rupture starts to take place with the “widowhood”, or perhaps delegitimization of every government. Shorn of uniqueness, access to this crack of lightness is approached by way of conceiving of oneself as a refugee. That’s how the light gets in. Solidarity of all humankind as Tikkun Olam, in its original pre-spiritual sense. This destruction of the rock to carve a stone eventually becomes a bell to ring, and that bell is democracy, real democracy. And for Cohen, that “Democracy”, as implied on his “First We Take Manhattan”, is already bubbling beneath the surface, beyond the darkness, in the belly of the beast, the USA.

Once again using what seems like an adaptation of a pre-set synth pattern, Cohen lays out, finally, what that new world from the ashes of the old may look like to us. Deliberately opening up his case that even the most limited democracy is won from below, he begins with an internationalist reference to Tiananmen Square. He makes references to AIDS and homelessness before the first refrain. Then we run through his very Canadian idealization of American society. It is common for Canadians, as is well known, to think they are somewhat superior to Americans. A lesser known tendency is one to see what they have what we don’t. And yes, we may have a better welfare state, to a certain degree, but we don’t have the raw human material that exists south of the border. To give an example,

It's coming to America first

The cradle of the best and of the worst

It's here they got the range

And the machinery for change

And it's here they got the spiritual thirst

It's here the family's broken

And it's here the lonely say

That the heart has got to open

In a fundamental way

Democracy is coming to the U.S.A

There are drunks, there are Christians babbling about Jesus that he “doesn’t pretend to understand”. Otis Redding is alluded towards, and even Chevrolet is a cheap but nevertheless compelling rhyme for “USA”. Democracy comes from the streets, which are “holy” and multiracial. The music video and the even the use of synthesized flute make use of national-popular American iconography but not in a pseudo-patriotic way. Rather it is one in that, the cycle of demiurge who is all knowing but powerless escapes to instantiate themselves as a priest, yet the only way to fight the murderous future is re-enchantment of sorts. And this comes in the form, in this case, of the messianic quality of the masses. What is the messianic age, after all, if not the masses, and in particular, the working classes becoming aware of their own power. And in that set of circumstances, things they slide, slide in all directions.

Of course this isn’t all to say that Cohen is any more coherent than he needs to be. He sheds light, while not without showing underdeveloped and even contradictory thoughts, here and elsewhere. Of course, it should be noted (as there will be another entry on Cohen’s work), that this is far from the only record in which Cohen exhibits profundity in a prophetic sense, as befits his lineage. In a sense, it is the music here. That perfect mix of schmaltz and goth, gospel and synth-pop. This appealed, of course, to Trent Reznor in his extensive use of this record in his score for Natural Born Killers. And more to the point, it sonically captured the moment as effectively as the lyrics and Cohen’s haunting vocals. In the end, it’s just a record, believe if if you need, or leave it if you dare. That being said, as a politicizing 15 year old it meant a hell of a lot to me. Yet we’re all still waiting for that miracle.